Architectural Development of Esher Place

Wayneflete Tower was constructed in the 15th century, however, the recorded history of the site on which it stands commenced some 400 years earlier. Esher was en route from Winchester to the Bishop’s London palace, Winchester House, Southwark and formed an ideal halting place, as it was situated close to the city, yet outside its boundaries. The Bishop’s itineraries show a regular commuting pattern between these two seats and Esher was clearly favoured as a rural retreat. Esher was therefore particularly important as the nearest residence to Winchester House, located within the diocese and with easy access not only for diocesan affairs but also for attendance at Court, at either Westminster or Windsor. In 1447, William Wayneflete succeeded Cardinal Beaufort as Bishop of Winchester and it is from this moment that he is linked to the Palace of Esher.

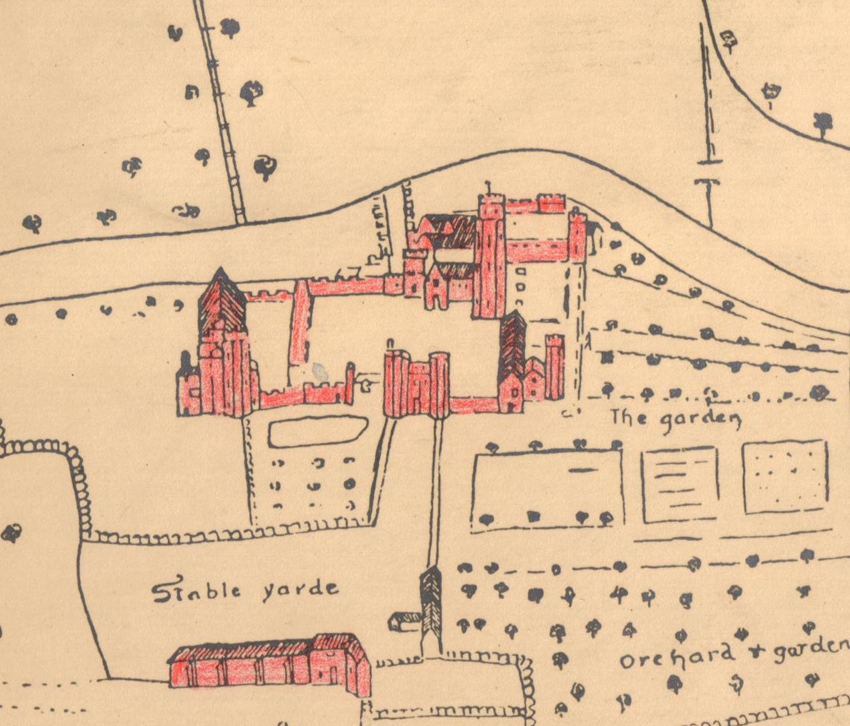

An early 17th century plan by Ralph Treswell outlines the structure of the palace. The drawing shows that the Tower was the gateway to a complex of buildings that surrounded a central courtyard, typical of a late medieval plan. The sole surviving structure of this complex is the gatehouse, known today as Wayneflete Tower.

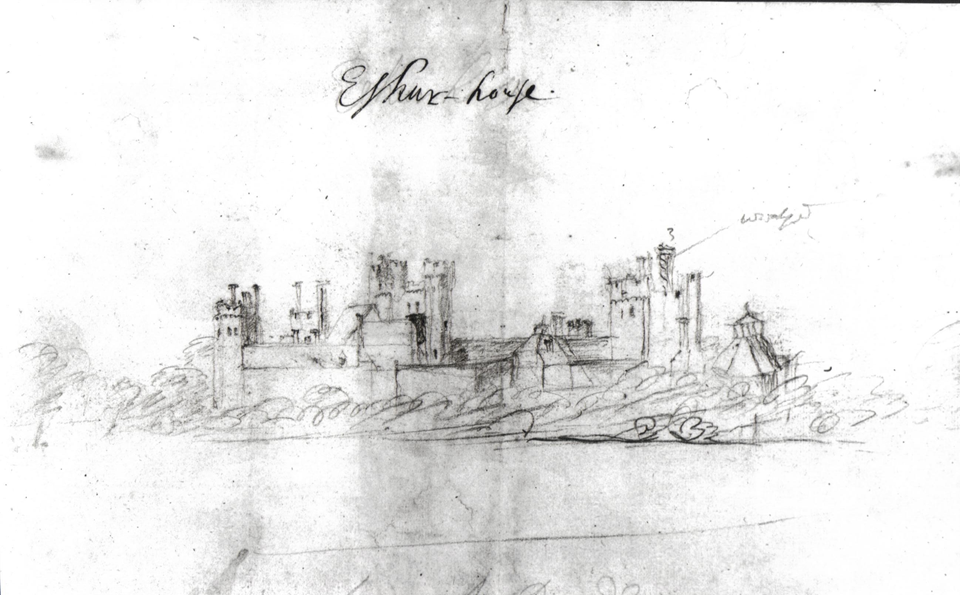

With the exception of the pipe rolls, the earliest surviving descriptive account of the Palace of Esher was by John Aubrey (1626 – 1697). Aubrey began his “Perambulation of Surrey” in 1673, the year in which he visited Esher and two centuries after Wayneflete’s building campaign. This sketch entitled “Eshur House” illustrates the substantial “castle-like” palace that would have been visible for miles. Aubrey noted that Wayneflete had erected a “stately brick mansion” on the banks of the Mole, within the park of Esher and described it as “a noble house, built of the best burnt brick that I ever sawe, with a stately gatehouse and hall.”

Following Wayneflete’s death in 1486, subsequent bishops maintained the property at Esher, but no significant building works were carried out until the election of Cardinal Wolsey to the see of Winchester in 1529. Prior to this date, Wolsey had been a regular guest of Richard Fox, (Bishop of Winchester, 1501–1528), at Esher, as it was a perfect retreat from his vast building project at Hampton Court. Esher was also a highly desirable property as its proximity to the Thames enabled easy access to the nearby residences of the King at Windsor and Richmond, which became increasingly crucial to Wolsey as he suspected his impending demise.

During his period of prosperity Wolsey had commenced the remodelling and significant enlargement of Wayneflete’s palace. Wolsey erected a long gallery constructed in timber at Esher. Its position is unknown, although it was probably sited along the riverbank to the north where the gardens and countryside beyond could be fully appreciated, with no compromise of loss of light in the Great Hall. The gallery was dismantled and carried to York House for re-erection there. The keeper of Esher Place was paid four pence in April 1531 “for his diligence in helping the workmen there …” It was evidently timber framed, for 105 tons of framed timber was transported to Thames Ditton and then sent by river to the site at Whitehall. The gallery was set up as the Privy Gallery of Whitehall Palace – which later became the spine of the whole complex. It seems from the evidence of the Whitehall building accounts, that the gallery was split into two parts, one either side of the gatehouse, which has become known as the Holbein Gate.

Following Wolsey’s departure from Esher and the subsequent final loss by the Bishop of Winchester of this seat in 1582, there is no recorded building development to the property for the next one and a half centuries.

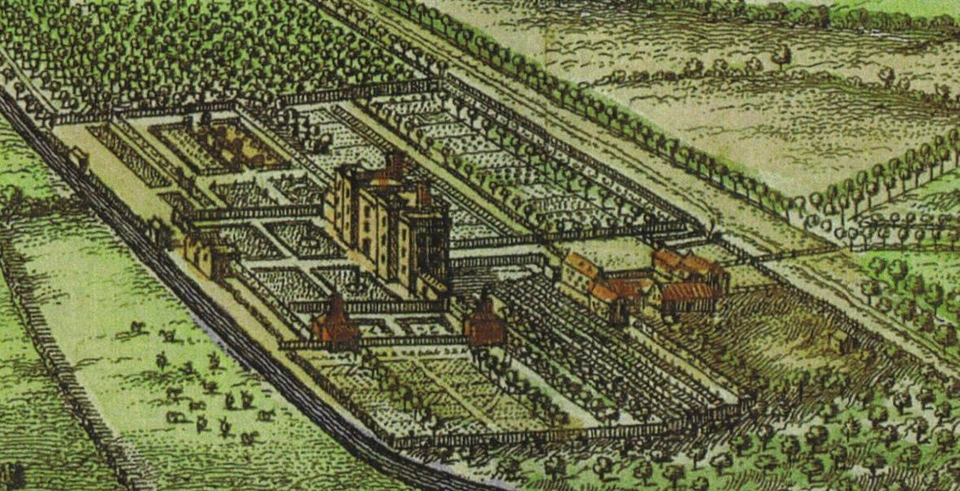

In 1677, Sir Thomas Lynch, a sugar baron and Lieutenant-Governor of Jamaica, purchased the estate and either during his ownership or that of his son-in-law, Thomas Cotton, the palace as recorded in 1673 by Aubrey had gone. Only the gatehouse survived, to become the core of a Jacobean residence, flanked by three-storey wings and this major redevelopment marked the second architectural phase of the gatehouse. The Kip-Knyff engraving, published in 1707, dramatically illustrates this almost unrecognisable transformation.

In 1730, Henry Pelham purchased the Palace of Esher and engaged William Kent, the celebrated architect and landscape gardener to make considerable alterations to both the house and the park, thus creating a property of magnificence that reflected not only his aesthetic taste, but also his political power and status. Kent’s talent, expertise and versatility are undeniable and he justly received great acclaim for his work at Esher.

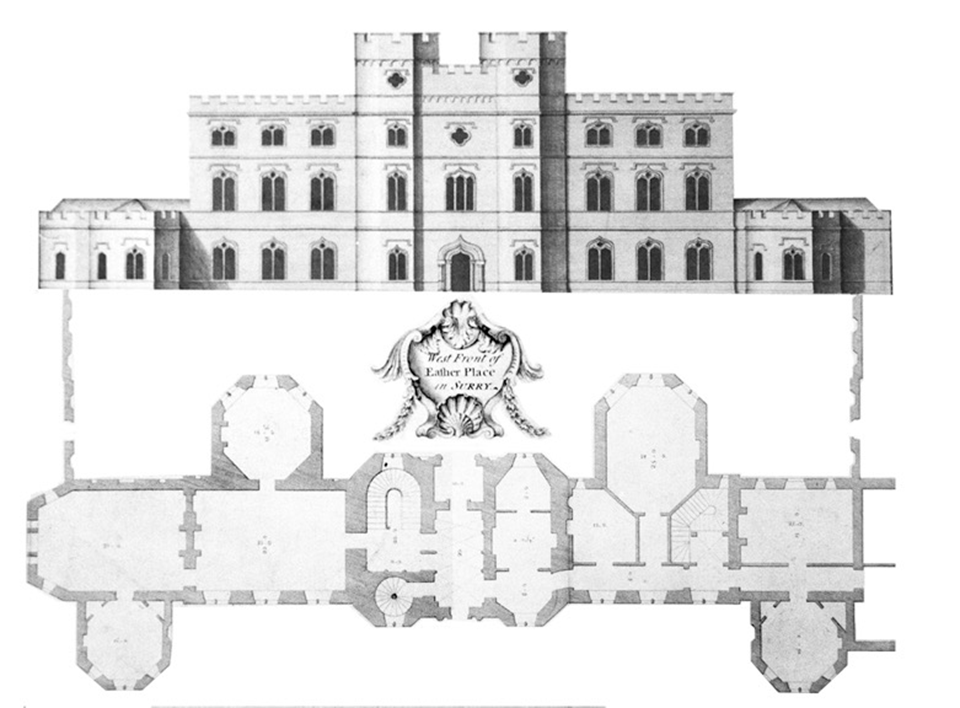

John Vardy’s engraved plan and elevation of Esher shows the attached wings with angular canted bays whilst the two pediments are of classical origin. At ground floor level on the west or river front the property is flanked with pavilions. No doubt Kent would have consciously designed and fully intended that the natural landscape, of which there was now no demarcation as it came up to the house, should be fully visible and appreciated; it is not surprising that so many windows were included for maximum effect and appreciation. For the first time the gatehouse had wings that returned away from the river on the landward side. The most contradictory element of his design is its strict symmetry that serves to highlight his love of Classical architecture. Kent’s decorative Gothick is rather glamorously inspired and evokes reflections of a romantic past. His treatment of the interior decoration was also lavish and fine examples of this ornamentation remain. His easy merger of Gothic and Classical architectural elements was simply the best recipe of the time and should be regarded as pioneering England through the 1700s.

In 1748, Horace Walpole wrote “Esher I have seen again twice, and prefer it to all villas.”

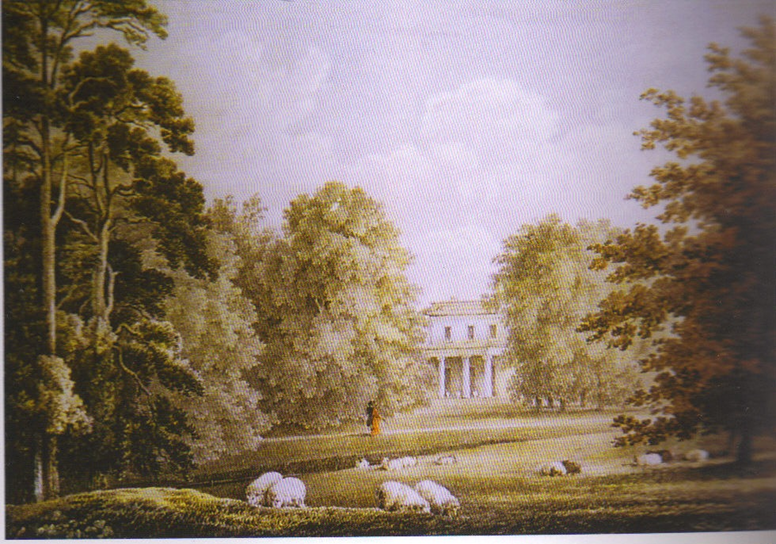

In 1805, John Spicer, a London stockbroker, bought the estate from Pelham’s heir, Lord Sondes and proceeded to demolish unceremoniously all the additions that Kent had made for Pelham, leaving Wayneflete Tower to stand alone as a monument to the past. Ironically, Spicer built a neo-Palladian house on the hill to the south east of the Tower – in the location and style that Kent had first proposed for Pelham. This new position provided the Spicers with a commanding view of the neighbouring countryside. The materials from Kent’s additions were reused to erect a brick mansion, stuccoed in imitation of stone where the Belvedere stood, which was also dismantled.

In 1893, Esher Place was sold at auctionfor £18,600. The new owners and residents were Sir Edgar and Lady Helen Vincent, who later became Lord and Lady D’Abernon. They proceeded to build the present house (now owned by Unite The Union) between 1895 and 1898. They employed the architects G T Robinson and Achille Duchene to build them the present Esher Place, an imitation of an 18th century French chateau. Spicer’s original house with stables and kennels was incorporated and formed the south-east wing, attached to a central block. The flanking wing consisted of an indoor royal tennis court which was paid for by the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII.

The economic slump that followed the Great War of 1914-1918 marked a period of neglect in the Tower’s history. The D’Abernons left Esher in 1934, leaving their property to the Shaftesbury Society for use as a girls’ school. Much of the remaining parkland of Esher Place including Wayneflete Tower was sold to Wayneflete Holdings Ltd, which developed most of the houses that exist on the estate today.

Despite being protected since 1925 by the Commissioners of Works under the Ancient Monuments Act, during this time Wayneflete Tower was somewhat forgotten, became the prey of vandals and was left to decay. Windows were broken, doors caved in and heavy coping stones hurled from the roof. Demolition was mooted and in 1938, having secured a six month option, the Council of the Surrey Archaeological Society launched a national appeal for funds to purchase the Tower from Wayneflete Holdings, who were still developing Esher Place into a private estate and hoping to achieve a sale price of £1,600. Few estates can have been divided quite so successfully. By giving just three months’ notice to the Office of Works, the owners, Wayneflete Holdings, were at liberty to dispose of this ancient monument.

With the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, understandably priorities lay elsewhere and the appeal proved abortive. However, mercifully destruction of the Tower was averted by Frances Day, a famous American film and stage actress and singer, who swiftly responded in the Tower’s hour of need and purchased the property jointly with Sir Raymond Francis Evershed on 7 November 1941, for £905. Her identity was initially withheld as she felt that: “[her] action in buying such a place might be misunderstood in these times”. Mr Evershed’s name appears on the deeds but curiously it seems that his involvement did not attract press coverage. She obtained the necessary licence to carry out renovations, to install drainage, water and other services, including a lift and permission to spend more than the war-time restriction of £100.