William Wayneflete’s career began rather modestly as Headmaster of Winchester College, a position that proved to be the most unlikely springboard for him to become Bishop of Winchester and Lord High Chancellor of England and therefore one of the most powerful men of the 15th century, owning no fewer than 240 properties. In 1447, William Wayneflete succeeded Cardinal Beaufort as Bishop of Winchester and shortly after founded Magdalen College, Oxford. The Bishop’s personal concern with the teaching of grammar was reflected in his foundation of two grammar schools, which both acted as feeder schools for Magdalen College, Oxford.William Wayneflete was also Provost of Eton College.

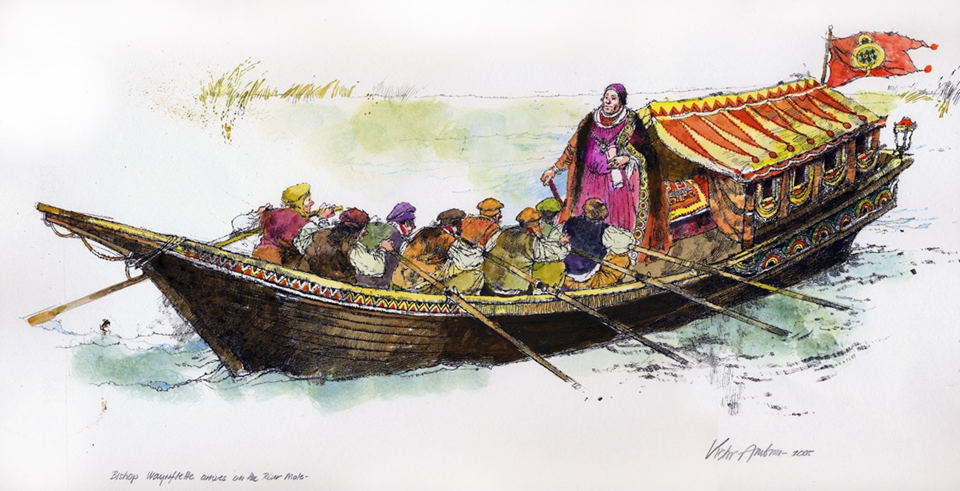

Esher was en route from Winchester to the Bishop’s London palace, Winchester House in Southwark and formed an ideal halting place. According to William Wayneflete’s bishopric itineraries (1447-1486) he first visited Esher from Southwark on 3 April 1448 and returned to Southwark five days later. A pattern of visits from Esher to Southwark and Westminster and occasionally Windsor and Eton were recorded until 1484, when Wayneflete was well-advanced in his years. From Esher it was possible to tender the River Mole or journey across land to the Thames at nearby Hampton Court and take a state barge, by far the most comfortable means of transport at the time, to London or Berkshire.

Rivers were an important consideration in the building of Episcopal palaces as they helped to ease the transport of bulky and heavy materials, including household provisions, visitors, servants and messengers. For many months of the year, and for many more centuries, the roads were too soft for wagons and the Thames provided an excellent link for attendance on the King. Esher clearly represented a desirable retreat not only from the Court, but also London’s pollution and noise, as the Bishop sought comfort, solace and tranquillity away from the stresses and strains of politics and the capital. The recurrence of plague at this time was most frequent in the towns and ports, where the flea-bearing rats multiplied, and these epidemics provided a further reason to escape to the country.

Today, the sole surviving structure of the Bishop’s Palace is the gatehouse, known as Wayneflete Tower. It is a four-storeyed building with semi‑octagonal projecting turrets to the front, which faces east, with splayed angled corners on the riverside; both front and rear faces have a decorative diaper pattern for which special vitrified bricks were used. These bluish-grey glazed bricks were made by fusing sand and the pattern contrasts well against the red brickwork. However, the effect would initially have been far more pronounced as the building would have received a protective red ochre limewash. The glazed bricks used to achieve the decorative diaper pattern would not have provided a key. Hence the limewash would have simultaneously enhanced the contrast between the bricks and the glazed diaper pattern, whilst also highlighting this striking and shimmering landmark which would have been visible for miles. Flamboyancy and gaudiness were enjoyed during the medieval period and well into the Tudor age. This diaper pattern, which is characteristic of Wayneflete’s buildings harks back to Eton, which represented the first major introduction of this design technique in England.

This imposing gatehouse symbolised the power of one man and effectively acted as Wayneflete’s frontispiece. It was intended to achieve the equivalent of our modern day “wow” factor, and its visitors would have immediately recognised the power, authority and importance of its builder.

William Wayneflete died at Bishop’s Waltham in August 1486 and was buried in the richly decorated chantry chapel of St Mary Magdalen in Winchester Cathedral. Following his death, subsequent bishops maintained the property at Esher, but no significant building works were carried out until the election of Cardinal Wolsey to the see of Winchester in 1529.

William Wayneflete’s career began rather modestly as Headmaster of Winchester College, a position that proved to be the most unlikely springboard for him to become Bishop of Winchester and Lord High Chancellor of England and therefore one of the most powerful men of the 15th century, owning no fewer than 240 properties. In 1447, William Wayneflete succeeded Cardinal Beaufort as Bishop of Winchester and shortly after founded Magdalen College, Oxford. The Bishop’s personal concern with the teaching of grammar was reflected in his foundation of two grammar schools, which both acted as feeder schools for Magdalen College, Oxford.William Wayneflete was also Provost of Eton College.

Esher was en route from Winchester to the Bishop’s London palace, Winchester House in Southwark and formed an ideal halting place. According to William Wayneflete’s bishopric itineraries (1447-1486) he first visited Esher from Southwark on 3 April 1448 and returned to Southwark five days later. A pattern of visits from Esher to Southwark and Westminster and occasionally Windsor and Eton were recorded until 1484, when Wayneflete was well-advanced in his years. From Esher it was possible to tender the River Mole or journey across land to the Thames at nearby Hampton Court and take a state barge, by far the most comfortable means of transport at the time, to London or Berkshire.

Rivers were an important consideration in the building of Episcopal palaces as they helped to ease the transport of bulky and heavy materials, including household provisions, visitors, servants and messengers. For many months of the year, and for many more centuries, the roads were too soft for wagons and the Thames provided an excellent link for attendance on the King. Esher clearly represented a desirable retreat not only from the Court, but also London’s pollution and noise, as the Bishop sought comfort, solace and tranquillity away from the stresses and strains of politics and the capital. The recurrence of plague at this time was most frequent in the towns and ports, where the flea-bearing rats multiplied, and these epidemics provided a further reason to escape to the country.

Today, the sole surviving structure of the Bishop’s Palace is the gatehouse, known as Wayneflete Tower. It is a four-storeyed building with semi‑octagonal projecting turrets to the front, which faces east, with splayed angled corners on the riverside; both front and rear faces have a decorative diaper pattern for which special vitrified bricks were used. These bluish-grey glazed bricks were made by fusing sand and the pattern contrasts well against the red brickwork. However, the effect would initially have been far more pronounced as the building would have received a protective red ochre limewash. The glazed bricks used to achieve the decorative diaper pattern would not have provided a key. Hence the limewash would have simultaneously enhanced the contrast between the bricks and the glazed diaper pattern, whilst also highlighting this striking and shimmering landmark which would have been visible for miles. Flamboyancy and gaudiness were enjoyed during the medieval period and well into the Tudor age. This diaper pattern, which is characteristic of Wayneflete’s buildings harks back to Eton, which represented the first major introduction of this design technique in England.

This imposing gatehouse symbolised the power of one man and effectively acted as Wayneflete’s frontispiece. It was intended to achieve the equivalent of our modern day “wow” factor, and its visitors would have immediately recognised the power, authority and importance of its builder.

William Wayneflete died at Bishop’s Waltham in August 1486 and was buried in the richly decorated chantry chapel of St Mary Magdalen in Winchester Cathedral. Following his death, subsequent bishops maintained the property at Esher, but no significant building works were carried out until the election of Cardinal Wolsey to the see of Winchester in 1529.